We have a thing called art and we have a thing called communication, and sometimes their curves overlap. (A lot of art does not have much to do with communication and a lot of communication has no artistic content.) In the middle there is something like an appleseed, and that is our theme―maybe our dream, too. (Nam June Paik, Random Access Information, 1980)

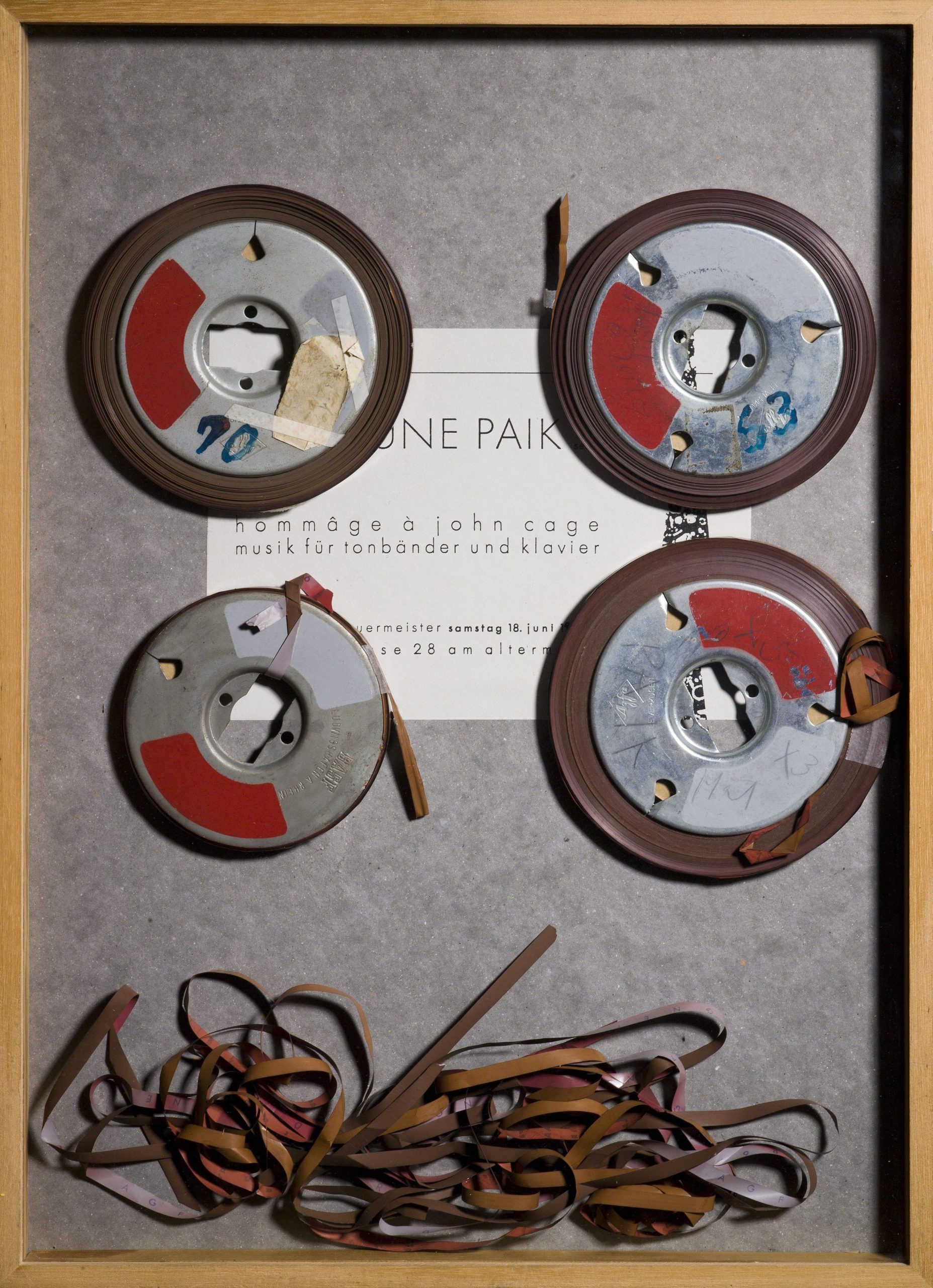

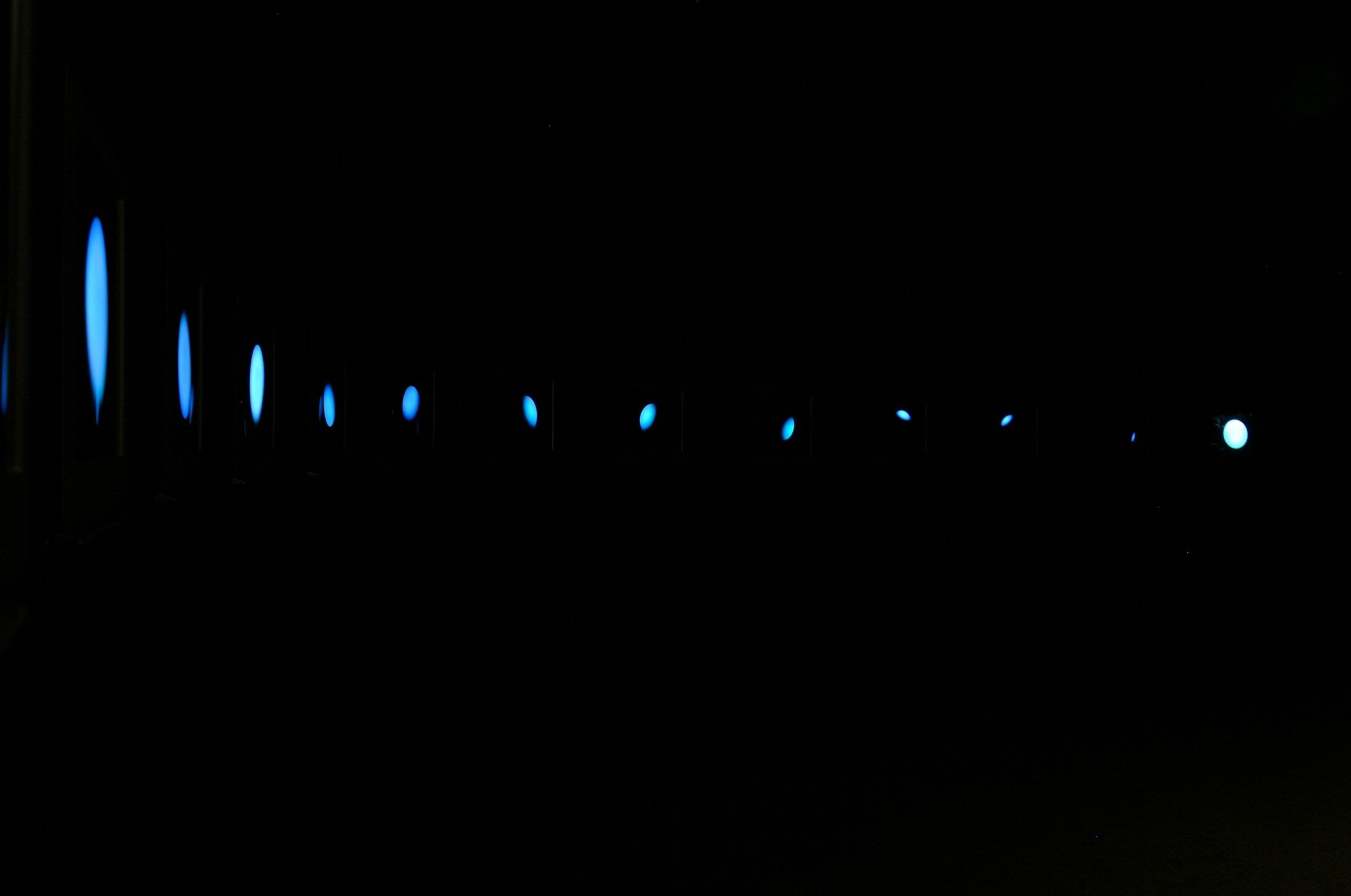

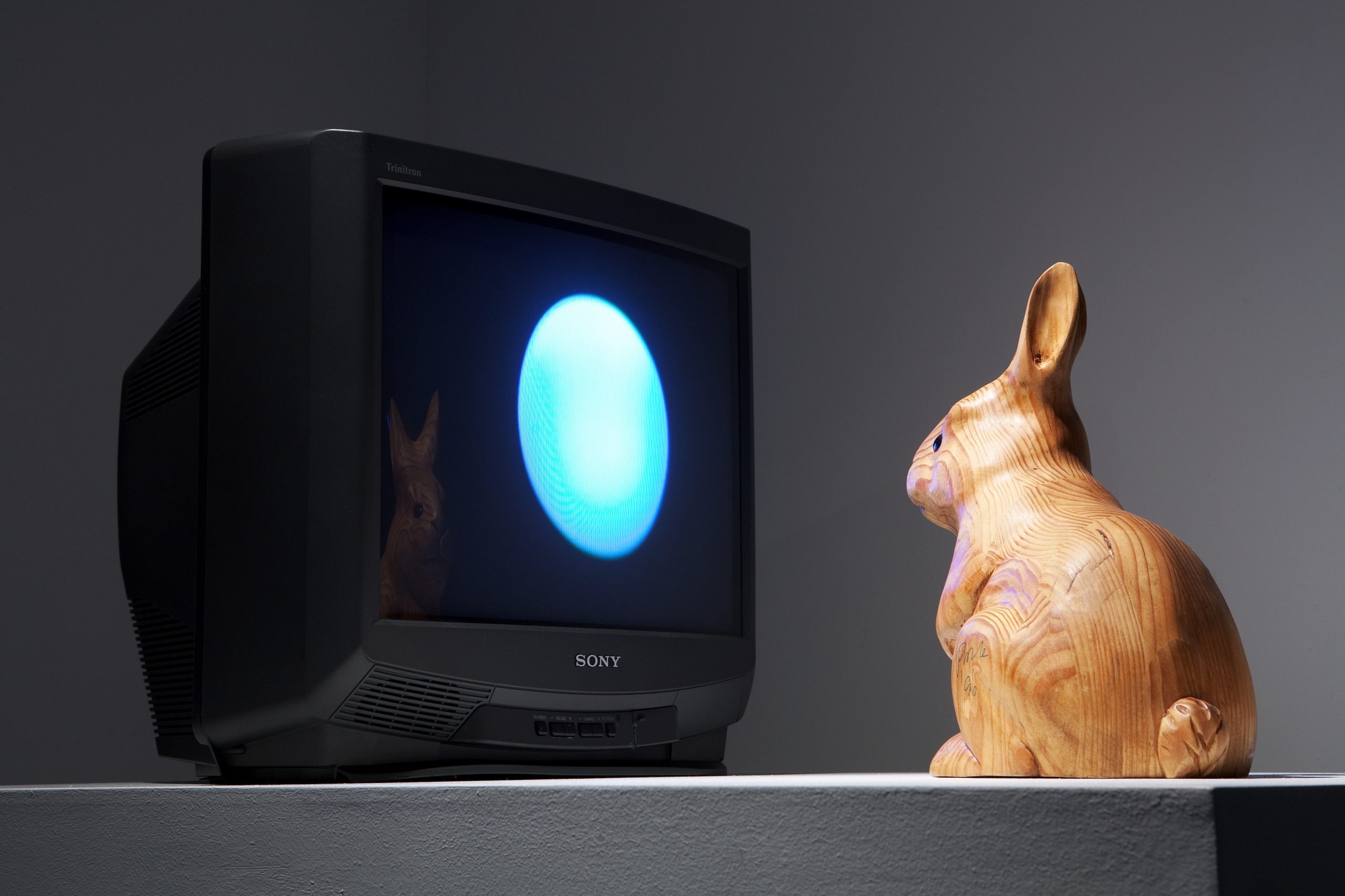

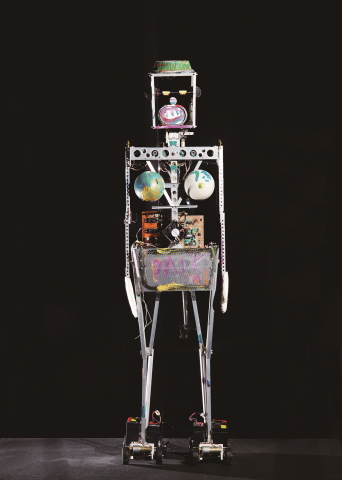

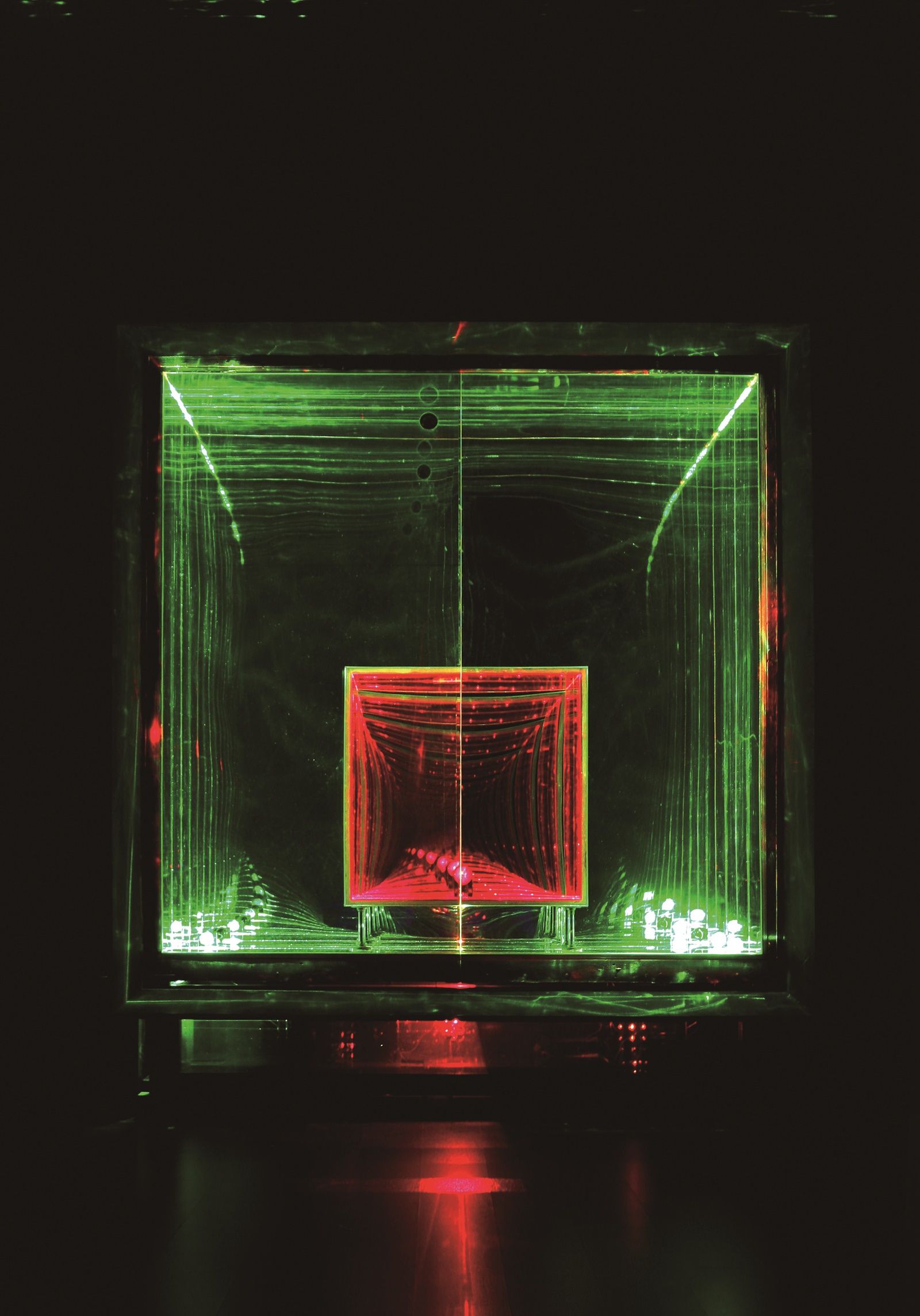

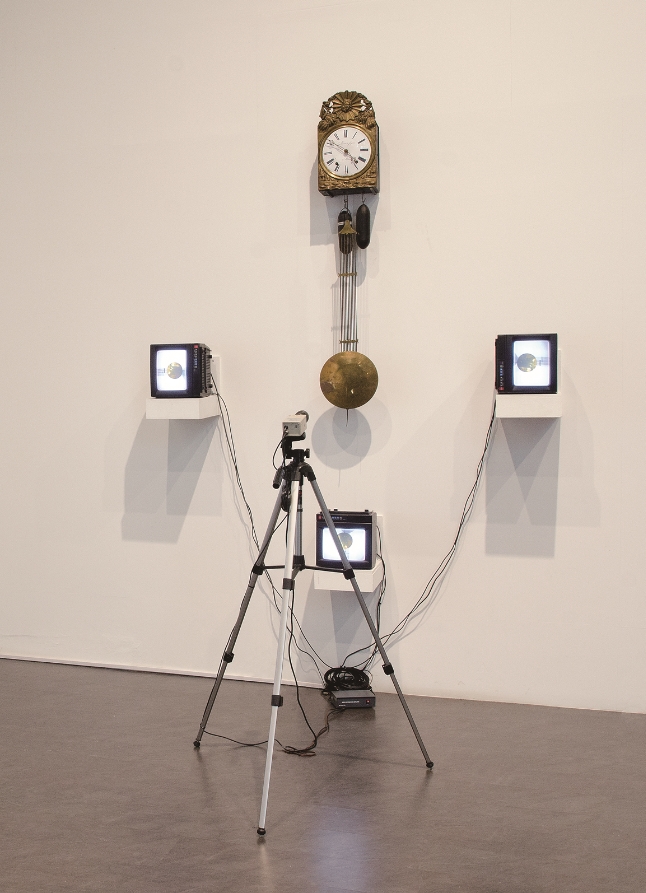

In March 1980, Nam June Paik gave a talk titled “Random Access Information” as part of the series Video Viewpoints, which was organized by curator Barbara London of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Contrasting with the magnetic tape playback approach of reading information sequentially, “random access” refers to the spontaneous reading of information in any desired location, as in computing. During his talk, Paik drew two overlapping circles, writing “art” in one and “communication” in the other. Where the two circles overlap, he said, was “something like an appleseed.” What sort of “seed” was it that provided this lecture with its theme, and that Paik himself described as a dream? The artist saw this seed as the potential harbored within video art. He believed that random access to video―as a means of recording and storing information from every moment in human history―was an important step toward overcoming problems of communication. To help this seed to sprout, he created video art by cutting and splicing information from the endless records of time. He also enabled more people to see his video work by broadcasting it not simply to museum visitors but to viewers of television, a medium that allowed for dissemination at an unlimited scale.

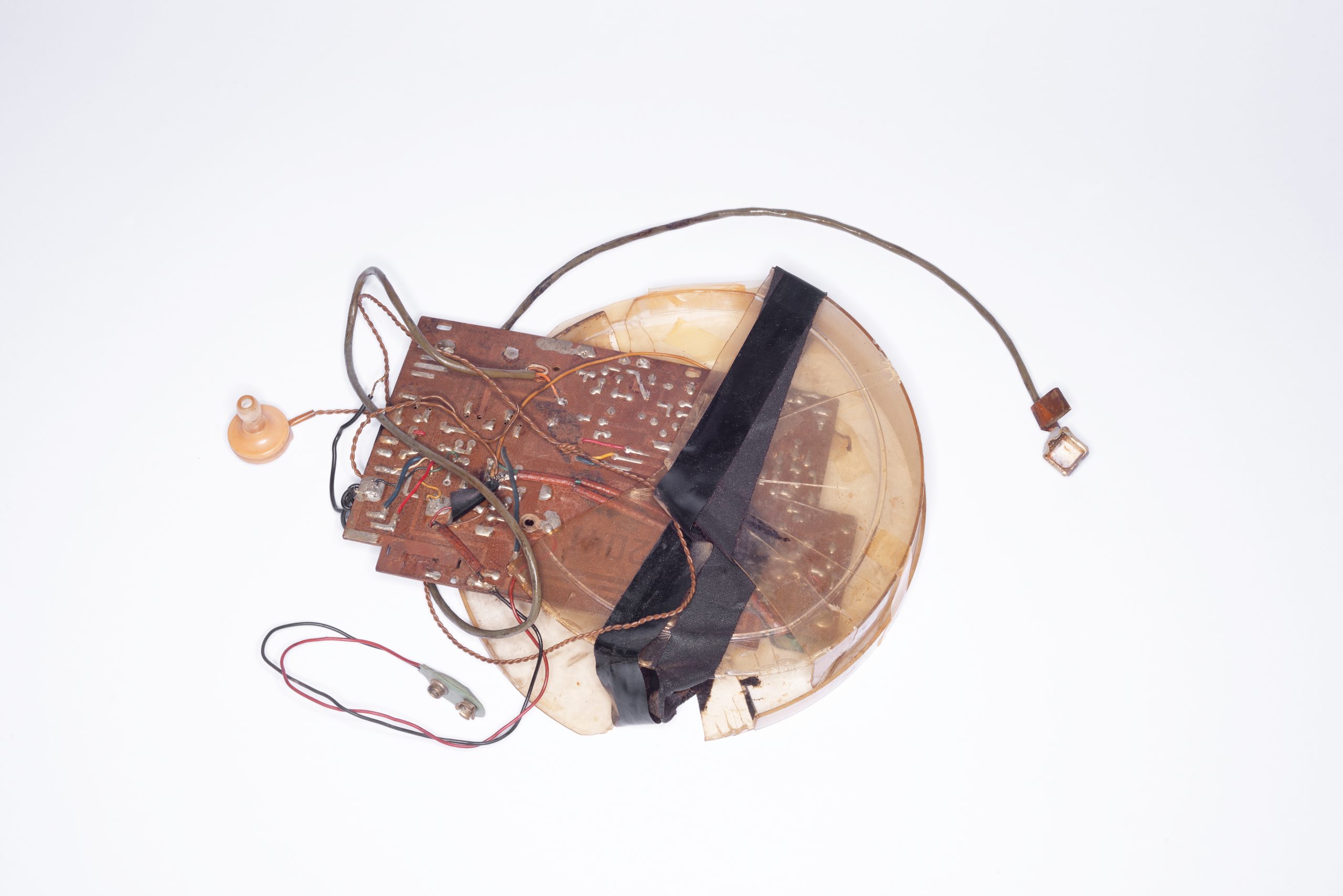

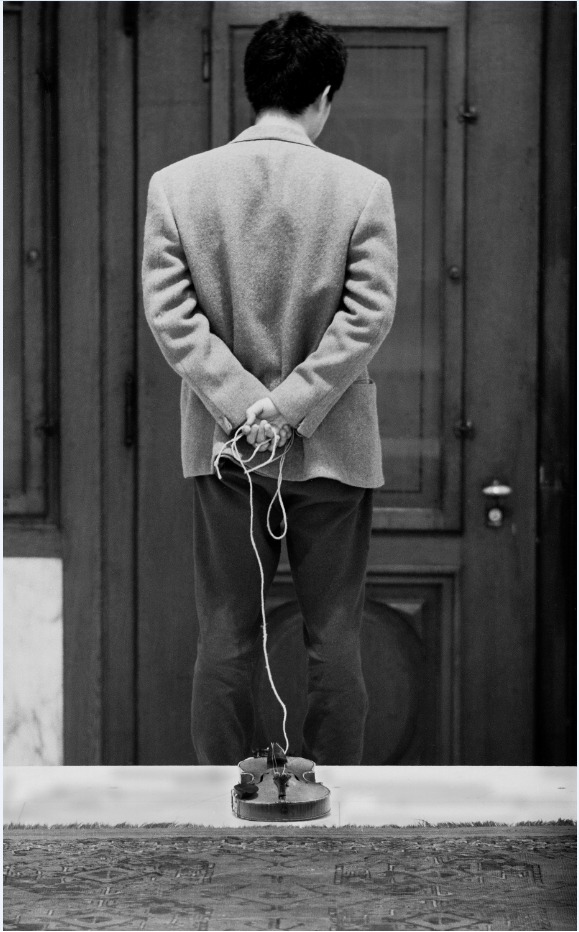

The biggest problem of communication is disconnection. When people are unable to meet and know one another, misunderstandings and prejudices build up, closing off the path forward. But as art and communication meet, they can become each other’s media. The methods of execution diversify as each becomes a powerful tool for the other, leading them to unpredictable places. Paik had already predicted that with its reorganization and editing of time, video artwork offered a way of transcending the bounds of time and space to connect people who had been unable to meet before and to create new relationships. He presented the work Random Access at his first solo exhibition in 1963, Exposition of Music – Electronic Television. It was designed so that viewers could scrape the desired portion of a magnetic tape to hear the musical information recorded on it―enabling the creation of sound through audience participation. The works of avant-garde art that Paik produced from the beginning of his artistic career exist as nutrients within that seed, which harbors all the unlimited potential for what may arise when video art―and art in general―intersects with communication. Today, we live in an era when we are no longer constrained by space or time: we can connect at any time, meet anyone, and form or discover any kind of relationship we want. It’s time for us to nurture Nam June Paik’s appleseed to sprout in a certain new way.